Φ ⋮ Seneca between Mailbox and Abyss

You might like to imagine Seneca as a leaden moral preacher lecturing from a slab of marble; instead, you find a man thinking about debt, power games, and sudden silence, while somewhere in the house a messenger waits for a reply and equanimity is hardly the dominant mood.

Δ ⋮ A Name in the Corridors of Power

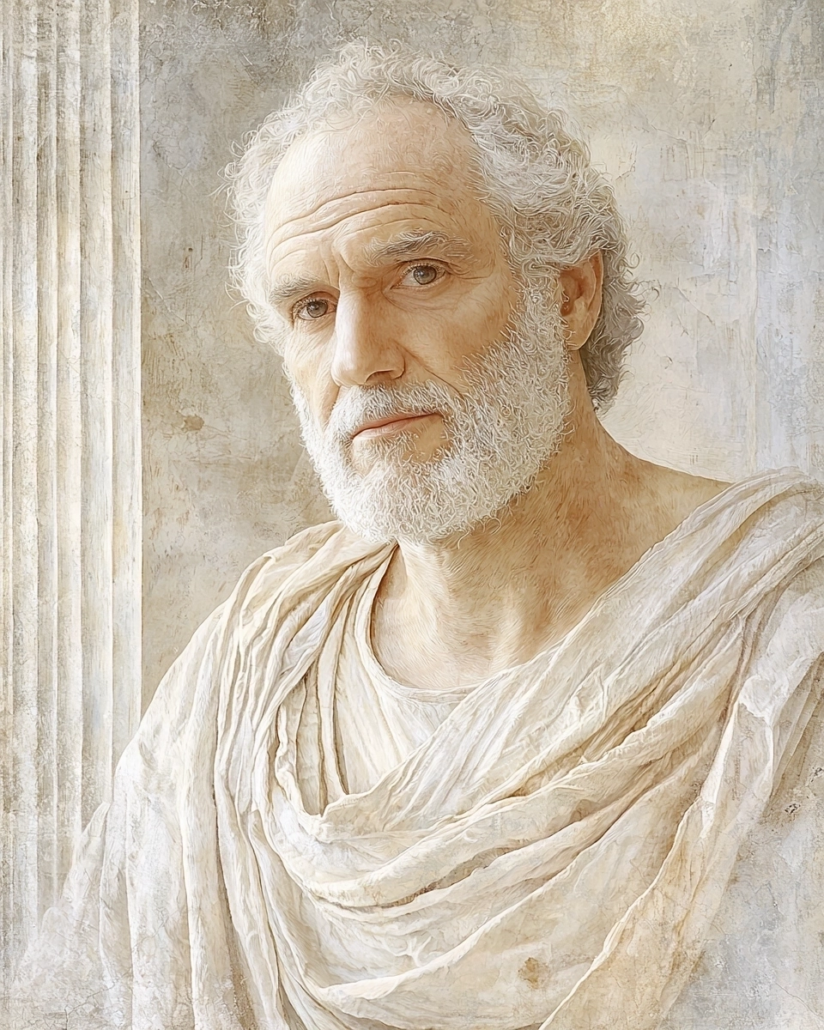

When you hear the name Seneca, a label usually sticks at once: statesman-philosopher, Nero’s tutor, martyr of reason, or accomplice of power. In Rome’s upper circles, one does not wear simple names; one wears roles, and Seneca carries several at once, like heavy cloth draped over the shoulders.

He comes from Hispania, yet his thinking unfolds at the epicenter—Rome, where voices are louder, corridors longer, and rumors faster than any courier. To call him a Stoic is less a label than a permanent test: amid the noise of an overheated capital, he tries to hold a tone that neither fully resonates nor fully falls silent.

You picture him more readily in a narrow workroom than in a heroic atrium: wax tablets, scrolls, a body already gnawed at by illness, and a proximity to power that feels more like a constant draft than a stable throne. His biography reads like a back-and-forth of ascent, exile, return, and voluntary withdrawal—no straight line, rather a series of corrections.

The Stoic affiliation remains present beneath this surface, without Seneca ever becoming a spokesman for a pure doctrine. He belongs to the late Stoa, Roman in tone, practically shifted, far more literary than his Greek predecessors. Instead of a system, he offers a voice that is at once strict and lenient—especially toward the human mishaps others prefer to hide.

In the background, there lingers the polite scandal that a man who invokes moderation, simplicity, and inner freedom lives amid wealth and political closeness. It is precisely this tension that makes him readable: Seneca does not pose as untouchable; he shows a person trying, amid gold and gossip, not to disappear entirely into the role.

Λ ⋮ Late Stoicism in the Spotlight

Seneca belongs to the late Stoa—not the original columned phase in Athens, but the Roman stage version, where philosophy and politics share the same corridor. The basic formula remains Stoic: a life in accordance with reason and nature, insight into the limits of external goods, and suspicion toward affects that move faster than thought.

His lifetime falls within a Roman epoch in which imperial power and senate perform a complicated duet. Exile, return, influence at court—Seneca moves through this field like someone who knows exactly how unstable every chair is that one sits on too confidently. The Stoic demand for inner independence thus gains less pathos and more urgency.

In his writings, he circles a few fixed points: the handling of time, preparation for the end, the art of enduring loss without tipping into noise or lethargy. Wealth, status, fame—all appear as provisional equipment, cancellable at any moment. What remains is character, provided it is not constantly leased out to others.

That he serves as tutor to the young Nero is biographical irony and philosophical provocation at once. Confronting a future ruler with Stoic self-discipline appears, in hindsight, like an overly ambitious experiment. Later, when the relationship collapses and Seneca is asked to take an orderly leave, his teachings on a calm death suddenly lose the safe distance of theory.

The central movement of his ethics nonetheless remains sober: virtue is not decoration but the only stable form of good; everything else belongs to the category of the indifferent, sometimes helpful, sometimes hindering, never reliable. That Seneca formulates these sentences in the presence of a court ruled by favor, suspicion, and mood sharpens their outline—as if written against his own surroundings.

Π ⋮ A Brief Pause with a Razor Blade

You could say Seneca preaches equanimity—until you notice how often his texts return to the thought that everything can break off at any moment, even in the middle of a carefully planned day; Stoic calm then means not that nothing happens, but that you cannot afford to fall apart every time it does.

Ξ ⋮ Everyday Life between Inbox and Street Noise

If you look for Seneca today, you find him less in a villa with columns than between doorframes and screen light. The kettle is still running in the kitchen; in the next room there is a video meeting in which five faces simultaneously pretend to be present. The day is full before it has begun, and no one asked whether you ever signed up for it.

Here, his Stoic thinking works like a casual counterfoil. He writes about the waste of time while you watch notifications settle over your day like layers of dust. It is not the events themselves that overwhelm, but the stories you improvise about them in real time: drama, offense, triumph—all at the speed of an updated feed.

Seneca would not comment on these scenes with a moral finger, but with a dry remark about ownership: what is truly yours when everyone constantly has access? Your calendar belongs half to others, your reputation hangs on channels you do not own, but your attention is the last piece of territory you can hold without a contract.

Within this setting, the Stoic concept of apatheia (freedom from overdriven affective reactions in the moment) becomes something inconspicuous and everyday: not a grand ideal, but the quiet refusal to log every email as an attack, every delay as an affront, and every sign of recognition as ultimate rescue. Stoic distance is then no shield of coldness, but a small gap between impulse and response.

Whether subway, open-plan office, or shared apartment hallway: wherever too many expectations are pressed into too little time, Seneca might whisper that not every invitation is a commitment, and not every mood needs a comment. The world remains loud enough even if you do not respond to everything that passes by.

Σ ⋮ How the Body Delivers the Punchline

Before a thought sorts itself out, the body has already issued its version: tense shoulders before a conversation, shallow breathing when a supervisor’s name appears on the display, a slight stab in the stomach when a message goes unanswered longer than you would like. Stoic practice begins where you notice this echo without immediately handing it the wheel.

Seneca writes about illness, exhaustion, physical vulnerability—not to romanticize suffering, but to show how tightly thinking remains bound to the body. When you lie in bed at night and thoughts run their “just one more time” loop, that is a modern variant of the same question: who sets the pace here, and who is merely riding along?

Breathing, posture, the minimal delay before replying—these are not esoteric rituals but small adjustments through which Stoic exercise loosens automatism. A deep breath before a difficult email does not change the world, but it changes the tone in which you perceive it. Seneca’s sober idea: not every inner alarm signal is a fire alarm; sometimes it is just a sensitive barometer.

The body provides no truth, only data. A racing pulse says something has become important, not that it is objectively catastrophic. Stoic practice reads these signals without pathologizing them: you register the tension, check the cause, sort before reacting. From the outside, the result looks like equanimity; from the inside, it feels more like well-organized unexcitement.

Thus emerges a psychophysical space of resonance in which Seneca’s texts are less textbook than mirror. You discover your own patterns in his descriptions—and notice that “inner freedom” is not a state one reaches and then manages, but a series of quiet corrections carried out together with the body.

Ψ ⋮ Seneca, Afterecho in the In-Between

At some point you realize that Seneca works less like a statue and more like a persistent background noise. He surfaces in self-help prose, in management seminars, in quieter books on dying and composure—often diluted, occasionally misquoted, but stubbornly present. The late Stoa has found its way into a world where hardly anyone still uses parchment, but almost everyone knows a waiting loop.

His texts are anything but smooth. Letters, treatises, consolations, tragic dramas—a mixing board that produces closeness and distance at once. You read intimate addresses to friends and still sense how much a role is at play: the philosopher commenting on the situation while standing right in the middle of it. The sources are rich and fragile at the same time, transmitted in fragments, filtered through copies, repeatedly rearranged by later centuries.

That is precisely why Seneca’s voice feels so strangely contemporary today. It knows the mismatch between claim and lived reality, between declared values and actual practice. He names illness, fear, loss without bathing them in pathos or consolation. The real luxury in his thinking is not time, but the manner in which you inhabit it.

In the background, one might discern a Stoic prokópē (idea of gradual progress without perfectionism): no breakthrough, no enlightened moment, but a sequence of small shifts. A slightly calmer word in the wrong place, a withheld comment, a mental dry run for what you will say tomorrow. Progress here is measured not in outcomes, but in a changed handling of what remains.

Of course, there is a countervoice. One can criticize Seneca for his closeness to power, for his wealth, for the gap between some sentences and his actual life. Perhaps it is precisely this gap that keeps him readable: you encounter no holy expert of unshakeability, but someone working on the same tensions you know between calendar, body, and conscience—only with sharper phrasing and a closer proximity to death.

“It is not that we have too little time, but that we waste much of it.”

– Seneca, attributed in the Letters on Time

If you want to read Seneca’s thought in condensed form, you can explore the stoic quotes by Seneca.

Ω ⋮ A Quiet Edge around the Present

At the end of this path with Seneca there is no certificate and no heroic transformation, rather a fine shift of perspective. The world remains loud, unevenly timed, occasionally absurd; only the inner commentary loses some of its urgency. What yesterday felt like a personal attack may today appear as a marginal note in a different plot.

You could say the late Stoa offers no escape from the present, but an alternative framing of it. The events change little; what changes is how they are sorted. Whether a day reads as defeat, imposition, or material for a better story depends, in Seneca’s view, less on external circumstances than on inner arrangement.

There is nothing spectacular in this arrangement. No grand gesture, no heroic renunciation, rather the quiet craft of observing one’s reactions before they dominate the room. Perhaps this is the unassuming core of his effect: he turns philosophy not into a high flight, but into a kind of discreet background technique that you tend to notice more when it is missing.

When you later encounter his sentences in other contexts—in therapy manuals, in quiet essays, in conversations about farewell and overload—it almost feels as if a thin Stoic edge has slipped between the lines. Not a shield, rather a slender line marking where you stop taking everything for self-evident simply because it is loud.

Perhaps what remains of Seneca in the end is just this: the possibility of living a day not differently, but differently framed; a small piece of distance between impulse and response, between noise and meaning, between outer clamor and the decision to inhabit one’s own present.

💬 Teaching fragments of the Stoa

Inquirer: I keep losing myself in trivialities. How are you supposed to keep an overview with all this noise?

Seneca: ✦ By first clarifying what is truly yours – and treating the rest as noise, not as a to‑do list.

Inquirer: I am afraid of wasting too much time and end up procrastinating even more.

Seneca: ✦ Time passes either way. The only question is whether you are present for it or just collecting excuses.

Inquirer: How am I supposed to stay calm when others constantly place expectations on me?

Seneca: ✦ Expectations belong to others, reactions belong to you. Never confuse ownership with something on loan.

Inquirer: And what if my body is already on high alert before I have thought anything at all?

Seneca: ✦ Take the alarm seriously, not literally. It reports importance, not truth.

≜ stoically reflected by Stay-Stoic

Reception & interpretations of Seneca

How Seneca turned from court philosopher into projection surface

Seneca has been reread for centuries – as moralizing court intellectual, as uncomfortable critic of his time, as quiet companion to experiences of crisis. The breadth of these readings explains why he keeps reappearing in scholarship, literature, and everyday discussions.

How has the view of Seneca shifted historically?

Ancient readers saw him mainly as a moral authority close to power; the Christian tradition read him partly as ally, partly as warning figure, while modern interpretations more often stress ambivalence, contradiction, and the gaps between declared ideals and lived biography.

Which modern thinkers take up his ideas?

Philosophers, essayists, and therapists draw on Senecan motifs – reflections on finitude, the use of time, emotional regulation, and calm – without always following him directly; often he serves as a contrast figure against whom they sharpen their own positions.

Which editions shape how we read him today?

The perception of Seneca is strongly influenced by selected translations, study editions, and annotated collections that each highlight particular aspects – letters, consolatory writings, or tragedies – and thus help determine which sides of his thought appear in the foreground.

Which open questions and controversies mark his current interpretation?

Current debates revolve around his role, wealth, and closeness to power, as well as the seriousness of his ascetic ideals; discussion ranges from readings that see him as inconsistent pragmatist to voices that regard these tensions themselves as a productive part of his philosophy.

Stoic Fact Sheet: Seneca

Structured research-based facts.

1. Name and variants

Full name: Lucius Annaeus Seneca, usually referred to in scholarship as Seneca the Younger (to distinguish him from his father, Seneca the Elder). In Latin sources he often appears simply as “Seneca”; modern reference works also use “Lucius Annaeus Seneca (the Younger)”. In Greek transmission he appears, among others, as Λούκιος Ἀναῖος Σενέκας.

2. Life dates & era

Born probably around 4 BCE in Corduba (today Córdoba) in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica; some standard works give a slightly different range around the turn of the era, so the exact year of birth is considered uncertain.

Died in 65 CE near Rome by forced suicide on the orders of Emperor Nero, in connection with the so‑called Pisonian conspiracy. Seneca belongs to the early Roman Empire (Julio‑Claudian dynasty) and, in literary terms, to the “Silver Age” of Latin literature.

3. Place within Stoicism

Seneca is regarded as one of the most important representatives of the late or Roman Stoa. Writing as a Stoic philosopher in Latin, he mediates the teaching of the Greek Stoa (Zeno, Cleanthes, Chrysippus and their successors) in a Roman, politically charged context. His writings are central for today’s understanding of the Roman Stoics and of later Stoic reception.

4. Historical context & role

Seneca came from a wealthy equestrian family (ordo equester); his father, Seneca the Elder, is known as an orator and teacher of rhetoric. Seneca grew up in Rome, received a broad education in rhetoric, philosophy and law, and became known early on as an advocate, orator and writer.

Under Emperor Caligula he was at times in mortal danger but is said to have survived through intercession at court. Under Claudius he was exiled to Corsica in 41 CE, probably for political reasons and in connection with accusations concerning Julia Livilla. In 49 CE he was recalled to Rome on the initiative of Agrippina and became tutor and advisor to the young Nero.

After Nero’s accession (54 CE) Seneca was for several years among the most influential men in the empire and acted as part of an informal circle of advisors around the emperor. From the early 60s onward he withdrew increasingly from politics, before being forced to commit suicide in 65 CE after the exposure of the Pisonian conspiracy.

5. Central themes & teachings

✦ Virtue: For Seneca, virtue is the only thing truly good; external goods such as wealth, rank, reputation, or health count as “indifferents” with merely relative value. What matters is inner stance, not outward success.

✦ Passions: Passions (ira, metus, cupiditas, and others) are, in Stoic terms, misguided judgments. The aim is not numbness, but transforming the passions through insight, self-examination, and practice so they no longer contradict reason.

✦ Time: In works such as De brevitate vitae and the Epistulae morales ad Lucilium, Seneca reflects intensely on life’s brevity, how to face finitude, and how to use the time available well.

✦ Providence: In texts like De providentia and the Naturales quaestiones, he links Stoic cosmology to the question of how fate, natural events, and human suffering fit within a rationally ordered world.

✦ Practice: Seneca stresses daily philosophical practice – reading, meditation, examination of conscience – and treats philosophy as guidance for living under political uncertainty, illness, and social pressure.

6. Teachers, pupils, key relationships

Teachers and formative influences include the Stoic Attalus, the Sextian Sotion and the rhetor and philosopher Papirius Fabianus. The exact chronology of Seneca’s studies can only be partially reconstructed and remains debated in detail.

His most famous “pupil” is Emperor Nero, whom Seneca first educates and then advises; their relationship shifts from pedagogical closeness to growing distance and ends with Nero’s order for Seneca’s forced suicide.

The Epistulae morales ad Lucilium are addressed to a certain Lucilius, probably a Roman equestrian and administrator. Whether he is a concrete historical addressee or a literary persona remains an open question in scholarship.

Seneca was also the uncle of the poet Lucan (Marcus Annaeus Lucanus). Their relationship seems to have deteriorated around the time of the Pisonian conspiracy; motives and details are only partly transmitted and remain to some extent speculative.

7. Major works

A substantial portion of Seneca’s work survives in the Latin original, though with text‑critical issues and some questions of attribution.

Philosophical dialogues and essays: Among them are De ira, De tranquillitate animi, De vita beata, De brevitate vitae, De providentia, De constantia sapientis and De clementia (addressed to Nero), as well as the consolatory pieces Ad Marciam, Ad Helviam matrem and Ad Polybium.

Letters: The Epistulae morales ad Lucilium (over 120 letters) are among the most important sources for the Roman Stoa and for Seneca’s self‑understanding as a philosopher.

Naturales quaestiones: A large work of natural philosophy that combines meteorological and cosmological observations with ethical reflections.

Tragedies: Tragedies transmitted under Seneca’s name include Thyestes, Phaedra, Medea, Agamemnon, Oedipus and Hercules furens. The authorship of some plays (especially Octavia and Hercules Oetaeus) is partly disputed.

8. Later impact & influence

✦ Late Antiquity: In late antiquity and the Middle Ages, Seneca’s moral writings were widely received; Christian authors such as Augustine, Jerome, and Boethius engage with him. For a time, the (now regarded as unhistorical) idea of a correspondence between Seneca and the Apostle Paul circulated.

✦ Renaissance: The Renaissance brought a strong rediscovery of Seneca, especially in the orbit of Neo-Stoicism (e.g., Justus Lipsius). His writings shaped humanism, moral philosophy, and early modern political theory.

✦ Modern era: In modernity, Seneca influenced essayists and moral philosophers (including Montaigne) and remained a central figure in how Stoicism is pictured in literature and popular philosophy.

✦ Debates: In current discussions of Stoicism, ethics, and psychology, his analyses of passions, evaluation, and self-practice are often compared with concepts in cognitive behavioral therapy, without claiming a direct historical line.

9. Attested quotations

“Life is long enough if you know how to use it.”

– Seneca, De brevitate vitae (Latin: “Vita, si scias uti, longa est”; exact section numbering varies by edition)

“Everything, Lucilius, belongs to others; only time is ours.”

– Seneca, Epistulae morales ad Lucilium (Latin: “Omnia, Lucili, aliena sunt, tempus tantum nostrum est”; letter numbering depends on the edition)

“It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare, but because we do not dare, they are difficult.”

– Seneca, Epistulae morales ad Lucilium (Latin: “Non quia difficilia sunt non audemus, sed quia non audemus difficilia sunt”; precise location varies between editions)

10. Comment on the sources

For Seneca the overall source situation is comparatively good, since a large part of his philosophical writings and several tragedies survive in the Latin original. Biographical information, however, comes mainly from later literary sources (Tacitus, Cassius Dio and others) as well as from self‑references in his own texts and is therefore coloured by perspective.

The exact dating of individual works, details of his relationship with Nero and the authenticity of some tragedies (for example Octavia) remain disputed in scholarship or can only be treated as cautious reconstructions.

Quellen / Sources

Editorial portrait by Mario Szepaniak.

Further Stoic Topics – Philosophy, Virtues & Daily Life

Stoically surprised today.